‘The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald’ at 50: bell tolls, beacon lightings, and a Great Lakes memory that refuses to fade

Fifty years after the Edmund Fitzgerald went down in a violent Lake Superior storm on November 10, 1975, the Great Lakes community marked the milestone with packed memorials, solemn bell tolls, and a flood of remembrance tied as much to maritime heritage as to a song that made a regional tragedy a global story. Ceremonies on Monday drew large crowds along the lake, while churches and museums from Detroit to the Upper Peninsula paused to read the names of the 29 crew and ring out their memory.

50th-anniversary ceremonies on Lake Superior

At Minnesota’s Split Rock Lighthouse, the annual beacon lighting drew a sellout in-person crowd and thousands more watching remotely. As dusk fell, the light turned across the dark water and the crewmen’s names were read, each followed by the strike of a ship’s bell. Similar observances unfolded at Michigan’s Whitefish Point, near the wreck site, where families and mariners gathered outdoors in cold wind to hear the bell ring 29 times—plus once more for all Great Lakes mariners lost.

In Detroit, the Mariners’ Church—long entwined with the Fitz legend—held a special midday service for the 50th, a nod to the ritual that has comforted families since the week of the sinking. Across the region, historical societies staged talks, concerts, and book signings, including performances by artists with deep ties to the story. Attendance swelled this year; organizers estimated crowds in the low thousands at the largest lakeside observances.

Why the bell rings 29 times

The bell—physical or symbolic—anchors nearly every tribute. Each strike marks a life: the captain, Ernest McSorley, and the 28 crewmembers who never returned. Many services add a 30th toll for all who have perished on the inland seas. The ritual grew from intimate family remembrances into a shared regional language of grief, solidarity, and seamanship, especially potent on milestone anniversaries when descendants and former sailors reunite to trade stories and steady one another.

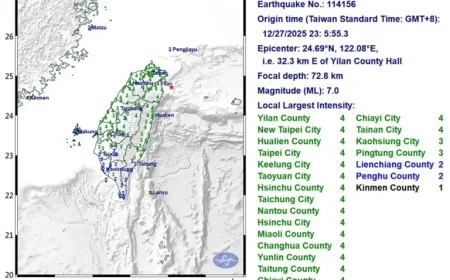

The final voyage, in brief

Launched in 1958, the 729-foot Fitzgerald was once the pride of the Lakes, hauling taconite from Superior, Wisconsin, toward the steel mills below Detroit. On that last run, gale warnings escalated into a brutal November storm. The Fitzgerald and the Arthur M. Anderson navigated in company as seas built and snow and spray cut visibility. Late in the day on November 10, the Fitz radioed that she was “holding her own.” No distress call followed. She vanished in deep water northwest of Whitefish Point; later surveys found the hull in two main sections on the lakebed. Debate over the exact cause—structural failure, rogue seas, shoaling—persists, but the resting place is treated as a protected grave.

The loss reshaped safety culture on the Lakes, accelerating upgrades to weather routing, buoy placement, crew gear, and reporting protocols. For mariners who worked those waters, the Fitz is not just a ballad—it’s a syllabus of what storms can still do.

How a ballad made a ship immortal

Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” arrived less than a year after the sinking, compressing technical detail and human ache into six vivid minutes. In the decades since, the song has become a seasonal rite; streams and sing-alongs spike every early November as listeners reinhabit the storm. On the 50th, that current only intensified—tributes, cover performances, and community listens turned up from harbor towns to big-city theaters. For many families, the song functions as public memory; for younger audiences, it’s the doorway into the history.

Art, endurance, and a living shoreline

What stood out on the 50th was not just scale but continuity. Lighthouse keepers who launched these memorials decades ago shared the stage with new voices, while museum curators unveiled projects designed to carry the story forward—oral histories from descendants, fresh exhibits on Great Lakes weather, and updated dives into the ship’s design and final trackline. Even athletic tributes joined the program this year, with long-distance swimmers and paddlers honoring the crew by tracing segments of the Superior shoreline in summer and returning for the November services.

Planning a visit or a moment of remembrance

-

Split Rock Lighthouse (MN): Hosts the annual beacon lighting each November 10 with readings of the crew names; advance tickets are essential.

-

Whitefish Point (MI): The lakeside memorial at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum brings families and mariners together within sight of the Fitz’s final path.

-

Detroit (MI): The Mariners’ Church offers an anniversary service with bell tolling; the sanctuary is open to the wider community.

If you can’t travel, many organizers now livestream their ceremonies and post recordings for later viewing. A simple alternative: read the list of the 29 names aloud, pause, and let a minute of quiet do what words rarely can.

The legend lives on—because people keep it alive

Half a century after the gale, the Edmund Fitzgerald remains less a mystery to be solved than a commitment to be kept—to the men who worked the Lakes, to the families who still gather under gray November skies, and to a community that believes remembrance is a form of seamanship. The bell tolls, the beacon turns, and the story crosses another dark water year.