Why Ange Postecoglou’s strategy didn't work: principles, personnel, and a clock that ran out

Ange Postecoglou arrived with a clear, attractive idea: dominate the ball, defend on the front foot, and compress the pitch with an aggressive line and inverted full-backs. It’s a philosophy that can sing when time, squad build, and habits align. At Nottingham Forest this fall, the pieces never locked together. Within eight matches the project ended, leaving a debate not about the beauty of the idea, but about its fit and feasibility in the circumstances he inherited.

The idea vs. the inheritance

Postecoglou’s football is principle-first: high defensive line, counter-press as the first form of defense, full-backs stepping into midfield, wingers holding width to stretch the last line. That model assumes three preconditions:

-

Ball security under pressure — press-resistant midfielders who can recycle cleanly against a high block.

-

Recovery pace — center-backs and a goalkeeper comfortable covering 40 yards of space behind them.

-

Automations — rehearsed rotations so the structure doesn’t collapse when one line is broken.

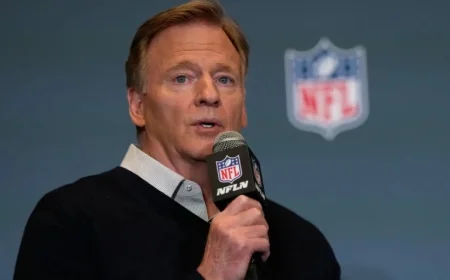

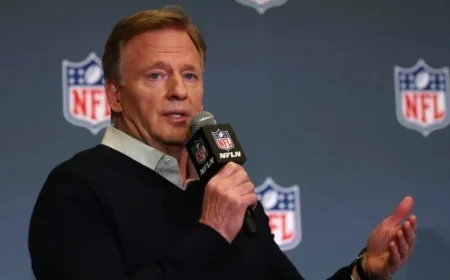

Ange Postecoglou out after 39 days at Nottingham Forest

Forest’s squad wasn’t built for that overnight. The center-backs were more dominant in duels than in long recovery races, and the keeper’s distribution under pressure fluctuated. Midfield turnover—both in personnel and positioning—meant the “rest defense” often lacked balance. When the first press was beaten, the box behind it was too big.

The high line without the high press

A high line only works if the press in front of it is synchronized. Too often the first trigger (usually a pass into a full-back or a six dropping between center-backs) arrived half a beat late. Wingers started from wider, deeper positions to respect the opponent’s full-backs, leaving the central press two-vs-three. That hesitation created a highway through the middle: one slip pass, one bounce layoff, and Forest’s center-backs were turning toward their own goal. The outcome wasn’t just shots conceded; it was field position conceded, forcing repeated long defensive sprints that drained legs and composure.

Inverted full-backs, exposed flanks

Inverting full-backs is powerful when possession is stable; it forms a 2-3 or 3-2 base that suffocates counters. But inversion is a risk multiplier if turnovers come in the wrong zones. Forest’s giveaways arrived in the half-spaces where the inverted full-back had vacated the touchline. Opponents immediately hit the channel behind the winger, pulling a center-back wide and unzipping the line. Without a single-pivot destroyer anchoring rest defense, those transitions looked like fast-breaks.

Fix that might’ve helped: If your six can’t defend the whole width, use a more conservative full-back on the far side (stay home, underlap sparingly) and stagger the line to create a built-in spare.

Build-up that invited traps

Postecoglou teams typically bait the first line to play through it. Forest’s spacing often made the bait too obvious: double-width center-backs, six dropping straight between them, both eights high. Opponents set simple pressing traps—curve run to the outside CB, screen the six, jump the return ball—and Forest funneled possession toward the touchline with limited exit routes. When the long release came, the front line wasn’t consistently structured to win second balls. Territory, again, flipped.

Alternative pattern: Stagger the six to a half-back lane (not dead center), drop one eight to form a back three in motion, and push the near full-back high only after the first line is broken.

No preseason, no patience

This model is choreography. It needs a preseason and a recruitment window tailored to roles: a sweeper-keeper who erases depth, center-backs with recovery speed and passing range, a six who protects both half-spaces, and wingers comfortable pressing inside-out. Postecoglou walked into a moving train—fixtures, pressure, and a thin margin for error. Early results created a feedback loop: score first or chase the game with the same risk profile, which magnified mistakes. In that environment, the “we learn by repeating the principles” mantra becomes a lightning rod when points don’t follow.

Game-state management

Another friction point was late-game control. Protecting a point (or a one-goal deficit) sometimes called for compacting space and killing rhythms with slower restarts, deeper lines, and lower-risk pass maps. Staying brave is admirable; in a relegation fight, game-state pragmatism buys time. Without those in-game pivots, narrow deficits became decisive and the table pressure intensified.

What might have made it work

-

Role-true recruitment: One rangy CB with elite recovery, one press-resistant six, and a goalkeeper comfortable sweeping 25–35 yards would have changed the geometry overnight.

-

Asymmetric full-back plan: One inverts, the far side stays connected to the back line until possession is stabilized.

-

Pressing triggers simplified: Fewer complex cues; pick two triggers (back-pass to CB, six receiving on the half-turn) and drill vertical jumps behind them.

-

Game-state modules: A “close the shop” shell—mid-block 4-4-2 for 10–15 minutes—to ride out bad momentum.

-

Set-piece emphasis: When open play is volatile, dead balls can carry you through a sticky month.

The verdict

There’s nothing inherently flawed about Postecoglou’s strategy. It’s demanding, and it exposes you if any link in the chain is weak: the press mistimed, the rest defense light, the goalkeeper hesitant, or the full-backs inverted without ball security. At Forest the gaps stacked—structural, personnel, and temporal—faster than results could buy patience. The lesson isn’t that attacking principles fail in the Premier League; it’s that context decides whether ideals take root or snap under the strain of the calendar.